Mt Kujū via Makinoto Pass, Kyūshū, JP

The Kujū Mountains (Kuju Renzan) are a range of active volcanoes in Aso-Kujū National Park, south of the town of Kokonoe, in Ōita Prefecture, Kyūshū. They are divided into the Kuju Mountains (in the narrower use of this name) and the smaller Taisen Mountains further west.

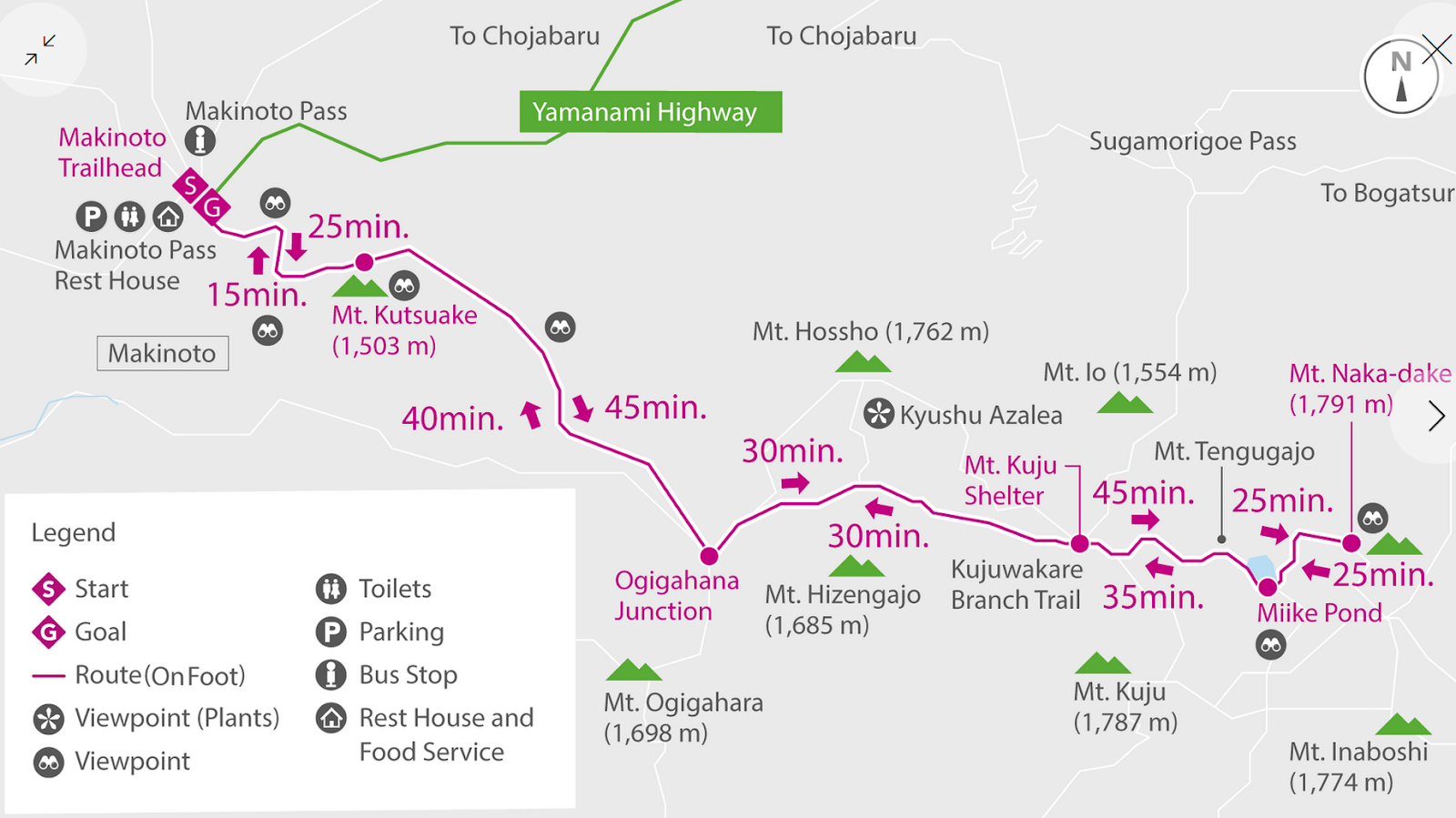

Many hikers aim for to the arc of peaks surrounding the crater pond Lake Miike: Mt Kujū (Kujū-san, a.k.a Kuzumi), Mt Inaboshi (Inaboshi/Inahoshi-yama), Naka-dake (Naka Volcano), and Tengugajo (Fortress of Tengu).

I took Kyūshū Odan Bus from Chojabaru Visitor Center to Makinoto Pass, ascended to the summits of Mt Kujū (1787m) and Naka-dake (1791m, the highest peak). After that, I crossed Sugamori Pass and descended to my accommodation near the visitor center.

During early spring, the Aso-Kujū reason has controlled vegetation burning to prevent trees from overtaking grassland. I happened to arrive before the burning in Kokonoe, but my next stop was Aso City, where the skies were somewhat hazy with smoke from local burning.

Access

Renting a car in Japan sounds challenging, so I relied on buses. The day before my hike, I took Kyūshū Odan Bus southwest from Yufuin bus terminal, along the Yamanami Highway, to the Kujū Tozanguchi stop. (Tozanguchi means trailhead.) Near the stop are Chojabaru visitor center and a few shops, described in the section just below my final video.

The next morning, I caught the same bus at Kujū Tozanguchi, going south to the next stop, Makinoto Toge (Makinoto Pass). The schedule said 9:52 Kujū Tozanguchi & 10:01 Makinoto Pass, but the bus was around 5 minutes late. The fare was ¥300; no change is given. They accept payment by cash or Kumamoto IC card, but not national IC cards like SUICA. Not sure about credit card.

This bus crosses alpine Kyūshū from Yufuin in the east to Kumamoto City in the west. It has space for large suitcases, and adequate leg room for tall people. I booked my two longer-distance tickets in advance at Beppu visitor center. There is no rest stop between Yufuin and Kujū Tozanguchi; if coming the other direction on the bus, from Kumamoto, there is a 10-minute rest stop at Senomoto.

Two other buses stop at Kujū Tozanguchi. All three timetables are in this gallery:

Time

The entire hike took me around 9 hours. This includes the time I spent resting and 20-30 minutes in total taking two wrong tracks (and returning to the right tracks). Without the bus in the morning, it might have taken an additional 1.5 hours walking uphill.

One map I saw gave 5 hours 15 minutes round-trip from Makinoto Pass to the high peak, Naka-dake, not counting rest. This map didn’t have my longer descent via Sugamori, or an estimate of the time to ascend Mt Kuju and go around the east of Miike Lake.

Route

The black Xs mark the Kyushu Odan Bus stops. I got on at the upper X, got off at the lower one, and followed the red line counter-clockwise. The short purple line shows my side-trip up to the high peak.

Map used under Government of Japan Standard Terms of Use (GJSTU).

The trailhead has toilets, a cafe (Makinoto Pass Rest House), vending machines, and a medium-sized parking lot. I began hiking at the trailhead to the left (east/northeast) of the cafe. The wind was very cold, and I was glad I had spent around 45 minutes in the cafe waiting for it to weaken. Forecast wind chill was -16 Celsius in the morning (30kph wind) but only -8 in the afternoon (10kph wind).

The trail starts up Mt Kutsukake (Kutsukake-yama) with steps. At the stop of the steps are benches under a roof. The trail then becomes a paved slope, before giving way to mud/dirt. There are a few patches of boulders that have to be clambered over. The first of these has some ropes to aid descent, although the descent is not steep enough for the ropes to be necessary. Mostly it was muddy, with some snow and some puddles, and the occasional patch of ice (often above a puddle). A rope fence on one side made the trail obvious. I took off my Kahtoola MICROspikes to better handle (footle?) the mud.

I mistakenly turned right for Mt Ogigahana, and then retraced my steps to take the left track. Unable to read the Japanese names signposted at the fork, I had assumed I was already at the next fork. When I truly did reach this next fork, I again turned right, because I wanted to avoid the ascent over Mt Hossho (Hossho/Hossyo-zan). After a long, flat, muddy stretch below Mt Hossho, I arrived at a clearing with a shelter and toilet. A minute beyond this clearing, uphill, is Kujū-wakare, an elongated four-way junction. The trail descending Mt Hossho joins the trail from the shelter, the trail to the high peaks around Lake Miike, and the trail descending toward Sugamori Pass.

Here’s an out-and-back route to Mt Naka-dake. I would have done this if I had had less time.

Map used under Government of Japan Standard Terms of Use (GJSTU).

I continued uphill toward Lake Miike, then went right at the next fork to ascend Mt Kujū. I did this so the sun would be behind me (to the south), lighting up Nake-dake and Mt Tengugajo (to the north) for photos. Two dark birds flew past, cawing at each other; they looked and sounded like the black kites I’m familiar with from coastal Japan. (A placard at the visitor center only mentions Eastern buzzards and Japanese sparrowhawks in the area).

After a rest on the bouldery peak of Mt Kujū, I took a different trail downhill to Shinmetsui, a swampy col. I could have continued east over Mt Inaboshi, but I decided to save time by turning north toward Naka-dake. A few minutes later, after passing a deer skeleton, I came to the next fork, and went uphill toward Lake Miike. This path was overgrown at first, but not too much. At the top of the hill, overlooking Lake Miike, is a stone shelter. From here, I went downhill briefly before going uphill for a few minutes to the T-intersection with the western ascent to Naka-dake and the eastern ascent to Mt Tengugajo. There is a trail that makes this short ascent easier, but I mostly missed it and clambered up boulders; on the way down I managed to keep to the trail.

Why didn’t I do big loop over all four summits? Because it was late winter and I had limited time before sunset. It would have taken 40-80 more minutes.

Back at the T-intersection between Mt Tengugajo and Naka-dake, I continued retracing my steps and returned to the stone shelter overlooking Lake Miike. Then I followed a path a few meters above the south shore of the lake.

At the next fork, I went right; going left would have taken me along a shortcut back toward Mt Kujū. Soon I was back at Kujū-wakare, where I began my descent toward Sugamori Pass on a moderately steep hill. This was the most difficult part of the descent, because the slope faced north, and thus had a lot more firm snow than I had encountered earlier in the day. I considered putting my Kahtoola MICROspikes back on, but decided not to bother, and reached the bottom of the hill without slipping.

Here began Kitasenrigahama (the untranslated 北千里ヶ浜 on the visitor center’s paper map). This is a gravel plain through a valley, with a stream crossing it. Yellow spray-paint on boulders indicate hikers should walk next to the stream, which makes for some very marshy ground after snowmelt. Here it was important to be wearing both boots and gaiters. Uphill to the left on Mt Iō (Iō-zan), I saw vapor rising from a solfatara, which I guess is to be expected, since iō means sulfur.

Eventually I came to the foot of the small bouldery slope leading up to Sugamori Pass. This hill took 5 minutes or so to ascend. The pass had a stone shelter, with a bell, and was even guarded by a small snowman. I also saw a few live deer, rather than a dead one, running away from me farther up on Mt Mimata (Mimata-yama), the peak to the north of the pass.

Initially I took a wrong turn down the formed stony track descending to the left, absent-mindedly stepping over the collapsed barrier meant to stop hikers walking there. After crossing a few old landslides obstructing the track, I check my maps app, and confirmed that this was a disused route. I spotted yellow posts in the distance below the pass on the southwestern slope of Mt Mimata, so re-traced my steps and descended there. This was a bouldery descent, with yellow spray paint again marking the way. Eventually the route crosses the valley, and one of several stone check dams built across the valley. On the other side of the valley, the route joins the formed stony track I previously took by accident, 40-50 meters below the place with the landslides. From here, the route was simple, and paved on-and-off. I passed the turn-off to Omagari trailhead and continued north toward the visitor center. There were several more deer, as well as a meadow bunting singing shortly after sunset.

Around 10 minutes south of the visitor center, I took a side-path down a small hill. It took me over a bridge crossing the small Shiramizu River. At the far end of the bridge was a T-intersection. Right would go toward the visitor center. I turned left, went up several steps, and took a gently sloping path uphill. Within a minute, I spotted an unmarked shortcut through five meters of woods to the road. My accommodation’s driveway was just across the road.

If 1 is an easy track, and 4 is using hands and feet on exposed rocks, I give this hike a 4 at worst. But the exposure tended to only be a few meters.

Makinoto Pass to Kujū-wakare

Kujū-wakare to the high peaks, and back

Kujū-wakare to Chojabaru via Sugamori Pass

Fuming solfatara on Mt Iō, beside Kitasenrigahama.

Deer run as a bird of prey flies.

Facilities in the area

The staff at Chojabaru visitor center and at my accommodation were both surprised to see a foreigner to show up without a car as the snow was falling in late winter, intent on hiking rather than bathing in the onsen. There is no convenience store, grocery store, or gas station. Within 3 minutes on foot from the visitor center, there are:

Resthouse Yamanami, which sells burgers, gifts, drinkable yogurt, and energy drinks;

a pizzeria;

a few Japanese restaurants, attached to onsen hotels, at least some of which are for guests only;

vending machines which sell the typical water, energy drinks, tea, and coffee;

a Montbell hiking store, which sells energy bars.

Chojabaru visitor center sells a paper map of the mountains, which is more detailed than any I have found online. The staff asked me if I had spikes for my boots. They did not mention the trekking pole caps they sell, which are meant to protect plants from the metal ends of trekking poles. Based on what they did mention and what they didn’t, I infer that they would rather hikers not slip on ice than protect fragile plants.

Pages about the Kuju Mountains

https://kujufanclub.com/en/ (visitor center)

https://kujufanclub.com/en/before-en (local transport and various agencies)

https://www.mountain-forecast.com/peaks/Kuju-Group/forecasts/1788 (the forecast I used - not sure if there is a better one)

this blogger recommends avoiding the obscure Hokotate/Hokodate Pass route (https://bizarrejourneys.com/hiking-in-kuju-mountains)

Pages about hikes from Makinoto Pass

east side of the road

Lake Miike

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-nakadake-ogigahana-junction-makinoto

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-nakadake-mount-tengugajo-makinoto

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-nakadake-mount-kuju-mount-inaboshi-loop

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-tengugajo-miike-pond

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/kuju-mountain-range-trekking-tour

also involving Chojabaru trailhead

also involving Omagari trailhead

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-hossho-makinoto

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-kuro-dake-mount-mimata-mount-hossho

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-ogigahana-makinoto

west side of the road

Pages about hikes from Omagari trailhead (on the road between Chojabaru and Makinoto Pass)

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-mimata-omagari-trailhead-loop

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/chojabaru-mount-mimata-omagari

Pages about other hikes from Chojabaru visitor center

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-hiiji-chojabaru

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/hokkein-onsen-mount-taisen-mount-hiiji-loop

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/mount-taisen-bogatsuru-wetland-chojabaru

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/bogatsuru-campsite-mount-mimata-chojabaru

https://www.alltrails.com/trail/japan/oita/bogatsuru-wetland-chojabaru-loop